Tales of the Itinerant Sailor

Cruising 2008

The Landlubber's Tale

By

"One if by Land, Two if by Sea"

Several months

ago I shared with family and friends my travels across the United States by

automobile last year over Thanksgiving through New Year’s.

I didn’t include photos as I had yet to download them from the camera.

Now that I have the photos, have enjoyed the memories they brought back,

I want to change the story.

The first

story was woven around going to new places while visiting nice people I don’t

see very often. Aside from the

warm, fuzzy feeling one gets while visiting family and friends, I really enjoyed

seeing sights/sites--some for the very first time.

|

|

New

England Coastal Scene. |

As I embellish

this story, I am relying on memory and the internet.

Not the best combination, I know.

Disclaimers aside, let’s start with Boston.

Oppressive

Taxation

As a student

of history, Boston has always held a special interest for me.

Of all the dissatisfaction within the colonies with the rules and

regulations imposed by the British after

There has been

much conjecture, explanations and theories of why this is so, researched by

well-educated historians much more erudite than I.

I could easily advance my own.

But when all is said and done, we would have just another theory.

|

|

Old

South Meeting Hall and Boston Skyline |

Boston is

where the first blood was spilt due to growing colonial resistance against

British rule. Parliament had imposed

a series of taxes on the colonies to help pay for the costly French and Indian

War. The colonists balked.

Aside from the monetary issues, the colonists protested a tax imposed by

a Parliament in which they had no representation.

“No taxation without representation!”

What a concept.

The Boston

Massacre

As the

resistance increased against these taxes, and to protect Loyalist interest, the

British military command sent troops to Boston in 1768, some of whom were

quartered in the homes of local citizens, with or without their permission.

Now we have another issued that agitated the locals.

This agitation culminated on March 5, 1770 when a crowd began throwing

snowballs at a British sentry in front of the Custom House on State Street in

Boston. Back up support was called

in; shots were fired; and five Bostonians died.

Thus, the Boston Massacre.

Protests were heard throughout the colonies and, some say, around the world.

Public opinion

was further incensed after the scene of this event was engraved by a silversmith

by the name of Paul Revere, which seemed to depict a British firing squad firing

point blank into a group of civilians.

This production, and later as

a courier for now what is being called the Revolutionary Cause, brought Paul

Revere into close contact with the real firebrands of this movement, John

Hancock and Samuel Adams (that’s right, the beer guy).

The Committees

of Correspondence

Communication

played a decisive role. Colonial

legislatures had appointed Committees of Correspondence during the 1760’s and

charged them with staying in touch with their counterparts throughout the

colonies. Obviously we are talking

about a hand written medium, not quite up to the speed of cell phones, text

messages and e-mail! The first

revolutionary use of these committees occurred in Boston, as you might have

guessed, on November 2, 1772 at a town meeting where it was voted to establish a

sub-committee “to state the Rights of the Colonists and of this Province in

particular” to the other towns and colonies.

Revolutionary talk, eh?

The Boston Tea

Party

This Boston

committee is accredited with organizing resistance to the Tea Act of 1773, the

only remaining import tax imposed by Parliament to help pay for the French and

Indian War. The British had

developed a scheme by which the struggling East India Company was granted a

monopoly to import tea to America, at a lower cost to the colonies as the import

duty was also reduced. Ships loaded

with tea for the colonies arrived subsequently in Philadelphia, New York,

Charleston and Boston. The lower

price was not an enticement; the colonists held firm.

No tea was off loaded (except in one instance where the tea was placed in

a warehouse where it remained until the end of the Revolutionary War).

But only in Boston was there a radical reaction.

After a mass meeting in the Old South Meeting House, it was decided that

about 200 of the men would dress up like Indians, board the three ships, and

throw the tea overboard. Which they

did, with no loss of life on either side, in part due to a well-organized

colonial plan and the capitulation of the merchants, who did not want their

ships to be vandalized. This really

pissed off the British, who closed the Boston Harbor to all merchant ships.

The British are Coming!

|

|

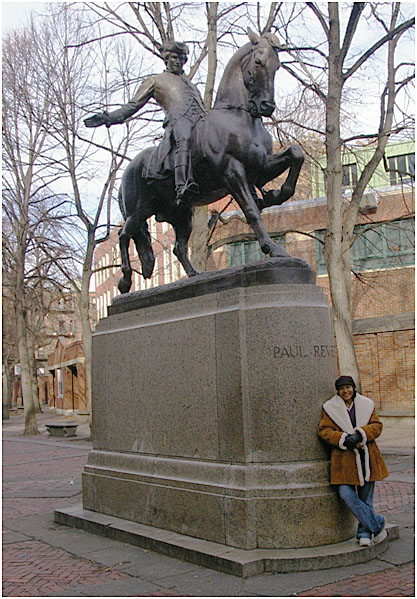

Statue of folk

hero Paul Revere. |

The people of

Massachusetts had begun to organize militias, for security purposes they say,

and to establish store houses for weapons:

Ammo dumps. In April 1775 the

British military command decided to raid the militia’s arsenal in nearby Concord

and to arrest the radical instigators Samuel Adams and John Hancock in

Lexington.

Anticipating

this, Paul Revere had put together a plan, with the cooperation of the sexton of

the Old North Church (Christ Church).

From the church’s steeple a signal would be sent by lantern to the

colonists across the river in Charlestown as to the movements of British

regulars: One lantern if the army

was moving by land; two lanterns would signal that the army was crossing the

Charles River first. From here, Paul

Revere, William Dawes and, later, Samuel Prescott would ride off into the night

to warn the villagers of this troop movement.

Along the way there were detained and only William Dawes made it all the

way to Concord.

But it is primarily Paul Revere’s name that is associated with this event. Why is this so? Because his home in Boston is still standing? Because it was his plan? Or is it because of the multi-verse poem penned by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in 1860, on the eve of America’s second great battle, the Civil War? Probably the latter, but at any rate the skirmishes between colonists and British regulars along the way and in Lexington and Concord become the first battles of the American Revolution. And for a fee you can visit Paul Revere’s house in Boston. Or you can click on the internet and read the entire poem for free.

|

Listen my children, and

you shall hear Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere. On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five; Hardly a man is now alive Who remembers that famous day and year. |

|

|

Looking for the

two lanterns hanging

“aloft in the belfry arch of Christ’s Church”—The Old North Church. |

The Battle of

Bunker Hill

|

|

“Don’t fire

until you can see the whites of their eyes.” At the Battle of Breed’s Hill, an American commander is quoted in order

to preserve what little gunpowder the colonists had. |

And this

begins the siege of Boston by British troops.

Colonial resistance forces were organizing from Massachusetts to the

Carolinas. In Boston British troops

under the command of Major-General William Howe wanted command of the high

ground of the city, especially Breed’s Hill (not Bunker Hill).

Learning of this, colonialists under the command of General Israel Putman

stealthily fortified both hills.

When the British mounted their attack, they were met by strong resistance.

Eventually, the British were victorious but at great expense, suffering

more casualties than any of the remaining battles in the years to come before

their final surrender in Yorktown, Virginia in 1781.

This misnamed battle, in effect, becomes the first battle of the American

Revolution.

So?

All of this in

order to postulate a question: Are there

injustices in our communities today that would prompt this same commitment to

resist authority, to organize and to take action?

A call to action? That would

cause us to take up arms (metaphorically speaking, of course) against those

causing the unjust treatment, whether they be in positions of authority of not?

To join a Tea Party? Think

about it as you down your first cup of coffee or sip your cocktail at pool side.

Well, enough

about history. Let’s get on with the

trip. Obviously, still by land.

| Changes at Rio Dulce | New York |

Cruising 2008: The Landlubber's Tale

Copyright © 2009 Steven Jones. All Rights Reserved.

Contact: siriusii@hotmail.com